Close to the bone: 3D printed implants

Visionary biomaterials and tissue engineer Hala Zreiqat has invented the world’s first 3D-printed porous synthetic bone, which mimics the mechanical strength of bones and promotes new bone growth. But her dreams of medical revolution don’t stop there.

Broken bones are often mended with metal plates or screws, but Professor Hala Zreiqat explains that metal was never designed to be part of the body. That’s why Zreiqat, Head of the Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering Research Unit at the University of Sydney, has developed a groundbreaking 3D-printed ceramic alternative.

The ceramic material mimics the bone’s properties, acting as a scaffold on which the body can regenerate new bone before gradually degrading. Trials have shown that it may kickstart new bone growth.

When Zreiqat’s invention becomes available, it could provide better treatment options for the millions of people worldwide who suffer bone loss due to injury, infection, disease or abnormal skeletal development.

Zreiqat imagines a hospital scenario where a trauma patient has their bone defect modelled from a CT scan. The model is fed into a 3D printer which prints the synthetic bone, to be immediately implanted by a surgeon.

“It takes only half an hour, max – that’s my dream,” says Zreiqat. “And we’re not that far from it, I don’t think.”

Zreiqat has been recognised internationally for her work, her commitment to promoting both early and mid-career researchers, and her championing of opportunities for women. In March 2018, she received the New South Wales Premier’s Woman of the Year Award for her contribution to regenerative medicine and orthopaedic research.

Zreiqat holds a slew of titles: she’s a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard University and Director of the new Australian Research Council Training Centre for Innovative BioEngineering, which is focussed on creating new implant technologies. She’s also a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellow, and she was the first female president of the Australian and New Zealand Orthopaedic Research Society.

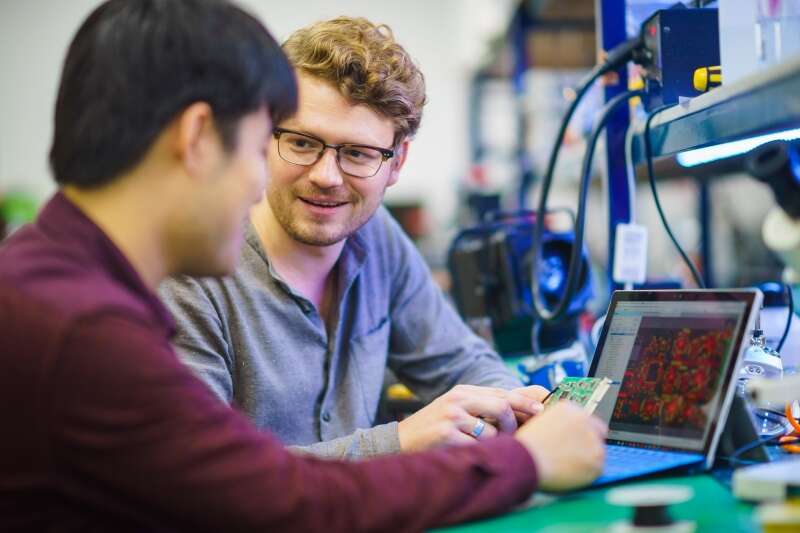

A proponent of multidisciplinary and cross-border collaboration, Zreiqat is also a Professor of Engineering and Medicine, and Co-director of the Shanghai-Sydney Joint Bioengineering and Regenerative Medicine Lab at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

An unconventional path

Profesor Hala Zreiqat © Australia Unlimited

Bethlehem-born Zreiqat was once an aspiring interior designer. “My office doesn’t reflect that at all,” she jokes. She grew up in Jordan, where she studied medical sciences; studying interior design would have meant moving to England.

After completing her biology degree, Zreiqat became a first lieutenant in the Jordanian army and began working as a scientific officer at the King Hussein Medical Centre. While leading a cardiac diagnostic lab there, she decided it was time to pursue her own medical research.

“Opportunities were limited in the Middle East, so I looked elsewhere, and Australia seemed like an attractive place. And I wasn’t wrong,” she says, still thrilled with her adopted country after 27 years.

Zreiqat’s PhD investigated how metal implanted in the body and bombarded with irons such as zinc and magnesium changed how bone cells behaved towards it. This work became the precursor to her revolutionary bone substitute.

In the years after completing her PhD, she received two major government grants. This support, combined with her boundless ambition, passion and intellect, propelled her along her career path.

“I think it’s amazing for the government to put trust in what [researchers] do and I can only hope the funding situation will become better and better in Australia, because we do have the talent,” she says. “If you look at it per capita, the discoveries [in regenerative medicine] coming out of Australia I think are on par with, if not better than, any other country in the world.”

In 2006, Zreiqat founded Sydney University’s first tissue engineering lab where she and her team continued their work in developing synthetic bone. The ceramic material has now been successfully trialed in rabbits and sheep, with human trials around the corner.

She is still thrilled with her adopted country after 27 years.

Opportunities were limited in the Middle East, so I looked elsewhere, and Australia seemed like an attractive place. And I wasn’t wrong.

A true trailblazer

With ambitious plans to change the world in more ways than one, Zreiqat isn’t wasting any time. She has supervised almost 70 PhD, Masters and Honours students, more than half of whom are women. In October 2017, during her prestigious fellowship at Harvard, she founded the IDEAL (Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Action, Leadership) Society, which launched on 11 June 2018. This international network, which has UN support, aims to improve opportunities and outcomes for women through education and policy change.

Zreiqat also hopes to travel to remote areas of Australia to inspire girls to study STEM subjects. “To change the way women are perceived … that’s my dream,” she says. “That’s where I would like to leave a legacy, other than inventing something.”

There’s little danger of Zreiqat not leaving her mark on the world. Her ultimate vision is to create a Sydney-based global institute where researchers from all backgrounds and academic disciplines come together to solve some of humanity’s greatest challenges.

“I will recruit all the top-notch young or mid-career academics to have fun and keep inventing and discovering for the purpose of humans. It would be a wonderful, beautiful place…”

Listening to Zreiqat leaves you with very little doubt that she will achieve each and every one of her grand visions.

Author: Ruby Lohman

First published on australiaunlimited.com