Australian Invention Seabin Tackles Ocean Pollution

On his travels around the world surfing and building boats, Turton was shocked by the amount of rubbish he saw floating in the world’s waterways.

Over a beer with his friend Ceglinski, he asked: “If we have rubbish bins on land, why don’t we have rubbish bins for the ocean?”

This simple question sparked the development of the Seabin, an innovative, world-first invention that is attracting global attention for its potential to help clean the ocean and revolutionise the health of marine ecosystems around the world.

Similar to a skimmer box in a swimming pool, the Seabin is an automated rubbish bin that collects floating rubbish, oil, fuel and detergents. It is designed for marinas, private pontoons, inland waterways, residential lakes, harbours, ports and yacht clubs. “It’s a little more complicated in the ocean than in a swimming pool, because you’re working with tides and waves,” says Ceglinski, who is Seabin’s Managing Director.

“But it’s pretty much the same idea. We’ve got a bucket-shaped container with a catch bag, a couple of different pumps suck the water into the bucket, the catch bag collects the rubbish and oil, and the clean water passes back into the ocean.”

World demand

Based in Perth, Western Australia, Turton and Ceglinski spent four years designing a prototype of the Seabin, with seed funding from Australian company Shark Mitigation Systems.

In late 2015, they launched the project on crowdfunding site Indiegogo. The campaign raised more than US$260,000 in two months and was supported by ocean lovers from around the world. Since then, they’ve gathered thousands of followers on social media.

“The project just took off. We had people contacting us from Australia, America, France … the whole world just went ballistic,” says Ceglinski. “At one stage, we were receiving 1,300 emails a day from people wanting to order the bins.”

In March 2016, Seabin announced an exclusive partnership with Poralu Marine, a French manufacturer of pontoons and marina equipment, to develop, manufacture and distribute the Seabins to customers worldwide.

“We’ve been approached by just about all the big marinas around the world,” says Ceglinski. “The city of Paris wants to put Seabins in the Seine, and the city of London wants to put Seabins in a couple of their marinas.”

The resort town of La Grande Motte became the first port in France to sign a collaborative research and development agreement with Seabin. Manufacturing of Seabins is due to start in September 2016. The first commercial Seabin will be installed at a marina in Portsmouth, UK, home to Britain’s America’s Cup sailing team in late 2016.

Giving rubbish a second life

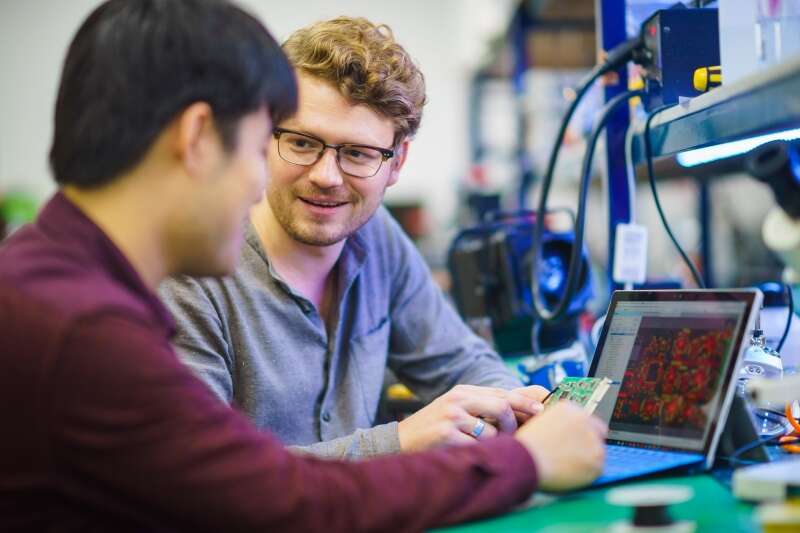

Co-founders Pete Ceglinski and Andrew Turton © Seabin

One of the challenges the Seabin team is addressing is what to do with all the rubbish the bins collect.

The amount of waste in the ocean and waterways is overwhelming. A report published in early 2016 estimates that the amount of plastic in the ocean will outweigh fish by 2050.1

“We only see 30 per cent of the rubbish in the ocean,” says Ceglinski. “Seventy per cent of it sinks. It’s pretty sad.

“We’ve worked out that if we collect one kilogram of rubbish per day, we’ll end up with nearly half a tonne of plastic at the end of the year – and that’s just from one Seabin,” he says.

To help address the problem, Seabin is partnering with Parley for the Oceans, a New York-based environmental group that will recycle the plastics collected by the Seabins to make other products. Parley for the Oceans has previously worked with Adidas to create shoes made from plastic collected from the ocean.

Turton and Ceglinski are also investigating how to use recycled ocean plastics to produce the body of the bins, making them more sustainable.

From marinas to the ocean

Both Ceglinski and Turton are avid surfers who grew up in Byron Bay, New South Wales, a town famous for beautiful beaches and lush bushland. Their lifelong love of the ocean drives their passion to keep it clean.

Turton is a boat builder and sailor, while Ceglinski started his career in industrial design before moving to the yachting industry.

When they thought it was “time to get serious” about the Seabin, they quit their jobs and set up a workshop on the Spanish island of Mallorca – there are about 2,000 marinas within a one-hour flight.

Their first goal is to have Seabins installed in marinas worldwide. Marinas have caretakers, who will be able to collect the rubbish. “It will make these marinas more efficient,” says Ceglinski. “It means the workers won’t have to spend six hours scooping out plastic and rubbish from the water each day. They can just empty the Seabin once or twice.”

The latest test version of the Seabin relies on electricity to run its pumps. But the team is working to develop a model that harnesses the energy of the sun to filter the water. This development began when they were approached by the Directors of the Balearic Islands in February 2016. The group of islands wants to eventually have solar powered Seabins in all of its commercial ports.

The next stage of development will be to get the bins into channels and bays. Finally, the men want to see them in the ocean, but Ceglinski says they still have some work to do before battling the full force of Mother Nature.

Clean ocean dreams

Making the catch bag © Seabin

Despite creating a product that has won worldwide attention, Ceglinski says they don’t want to have Seabins in the future.

“We shouldn’t have a need for them,” he says.

The men want to link education programs to young people with Seabins in their area. They hope that by creating awareness about pollution, the younger generations will become leaders of drastic, positive change.

“We’ve got a couple of marine biologists who are working with us now to set up data, education and research programs,” says Ceglinski.

“Eventually, we want to have an international database from the information captured in these Seabins to understand the path of the rubbish and how much we’re taking out of the ocean.”

The small Seabin team hasn’t slept properly since launching the crowdfunding campaign in September 2015, and their workload isn’t going to decrease any time soon. But Ceglinski says they’re energised by the amount of support they’re receiving from around the world.

“We’re stoked,” Ceglinski says. “We were both building boats for years and we never gave anything back to the environment. It’s really fulfilling to be able to do something positive.”

1 Report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation launched at the World Economic Forum.

Author: Imogen Brennan

First published on australiaunlimited.com