Diamonds are a Scientist's Best Friend

Dr Barnard is the first woman and the first Australian to win the Foresight Institute Feynman Prize for Nanotechnology (Theory), a pinnacle of achievement in the world of science. The prize is the latest in a string of prestigious titles Dr Barnard has accrued.

A world wonder

Dr Barnard’s soft Australian accent hints at a life lived on many continents.

When she was studying for her PhD (applied physics) in theoretical condensed matter physics at RMIT University in Melbourne, she was living in Toronto, Canada, and commuting back to Melbourne. She took just 17 months to complete her PhD.

She got the job, at the Argonne National Laboratory, a government lab in Chicago, USA. But after a couple of years, she left to work at the University of Oxford.

“One of the great things about science is our ability to travel, because science is the same language all over the world. Maths is the universal language that we speak,” she says.

A gem of a discovery

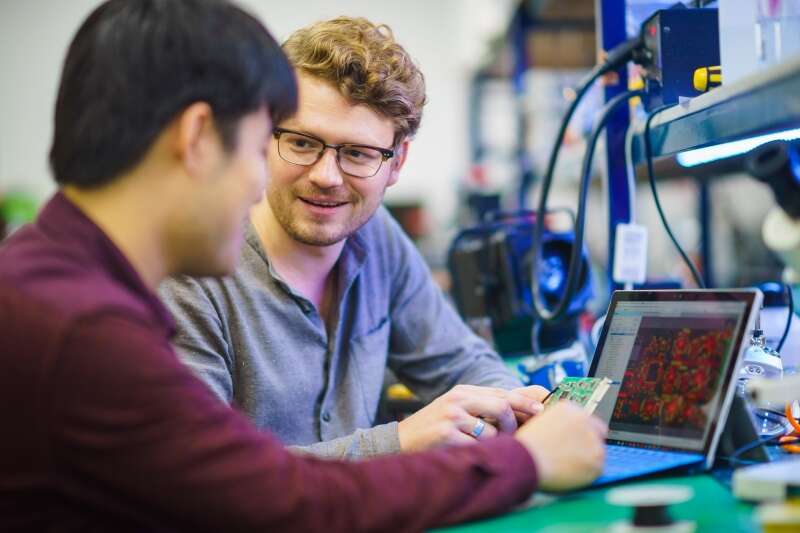

BNNanotube, Dr Amanda Barnard

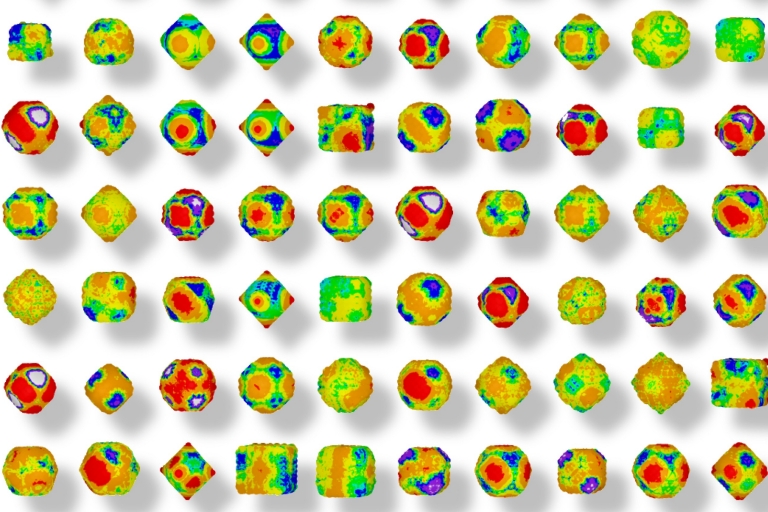

It’s hard to imagine something as tiny as a nanoparticle. They are one billionth of a metre in size and make up a sort of invisible world. About 15 years ago, Dr Barnard started using supercomputers to study them. It was the most brilliant gem that captured her attention: diamonds.

“I was thinking: let’s try to understand how the different shapes, sizes and structures of diamond nanoparticles can impact their stability and their properties,” she says.

Dr Barnard discovered that diamond nanoparticles have unique electrostatic properties that can repel or attract, similar to a magnet. She also found that their surfaces link up to form a porous aggregate, “like a very ordered sponge”. Her research is potentially life-changing for millions of people around the world.

For example, a study at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is investigating whether diamond particles can more effectively deliver drugs such as chemotherapy, insulin and gene therapy. Dr Barnard’s research underpins this work and her findings could mean that the amount of drugs needed to deliver the same treatment will be about 10 times less.

“We can target the disease better,” explains Dr Barnard. “It’s a slow release because of the porosity of the diamond particles and being able to have something like a ‘chemotherapy patch’ to deliver the drug slowly, over an extended period, will have less side effects.”

It was Dr Barnard’s years-in-the-making diamond nanoparticle discovery that secured her the 2014 Feynman Prize.

“It’s been great along the way to find out that my predictions have been proven correct,” says Dr Barnard. “But it’s incredibly rewarding to know that the applications it has found are ones that I really believe are going to improve the lives of patients in the future.”

Dr Barnard is the first woman to win the Feynman prize in its 22-year history – a promising development and one that this scientist accepts with deep responsibility.

“It was a bit daunting actually,” Dr Barnard says. “I really did feel incredibly proud that finally it’s gone to a woman – and that woman happens to be me. But now I do definitely feel a sense of duty for the sisterhood, to not let them down.”

Bringing knowledge home

Dr Amanda Barnard, Nanosolid nanofluid

Dr Barnard advises young scientists to gain experience – in life and in work – by travelling early in their career. But, she says, it’s crucial to bring their learning home.

After moving back to Melbourne in 2008, she took up a position with Australia’s national science agency, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). She draws on her experience gained from years of working abroad to collaborate with fellow scientists around the world.

“The days of clustering together in one city or one institution – or even one country – are gone. We work globally,” she says.

“Over the years of that diamond project, I worked with people in Russia, the UK, Italy, the United States, Japan and Germany. With electronic media these days, we can be in contact every day.”

Dr Barnard is motivated by the thrill of new discoveries, whether her own or those of the research team she now leads at CSIRO. She’s excited about the future. Where will her diamond research lead? Will her work lead to new technological advances? And will more women excel in science? There is much left for her to discover.

Author: Imogen Brennan

First published on australiaunlimited.com