On a Mission to Clean up Space

Professor Craig Smith has been passionate about astronomy and science since he was a child. Now, as CEO of EOS Space Systems, he’s helping build giant lasers to save space debris from collisions that would cause chaos in our communication and navigation systems on Earth.

In 2009, an active Iridium satellite and a dead Russian satellite crashed into each other, spawning 5,000 bits of space junk, which are all still floating around up there.

There’s now so much space debris that it could keep proliferating even if we never launched another object. That’s how much new flotsam the frequent collisions between existing debris are creating, according to Professor Craig Smith, Chief Executive Officer and Technical Director for EOS Space Systems says.

Increased space debris boosts the possibility of damage to space vehicles, shuttles and satellites, as orbits get more crowded. In 2014, the International Space Station had to move three times to avoid lumps of space debris.

“These things are travelling at 30,000 kilometres an hour, so even a collision with a very small one centimetre piece of space junk is enough to destroy a satellite,” Smith says.

And satellites play a role in almost everything we do these days.

“Communication, navigation, earth observation, timing … all the automatic tellers run off timing systems created by satellites, so if the satellite navigation sites went down, for example, all the banks would be crippled,” he says.

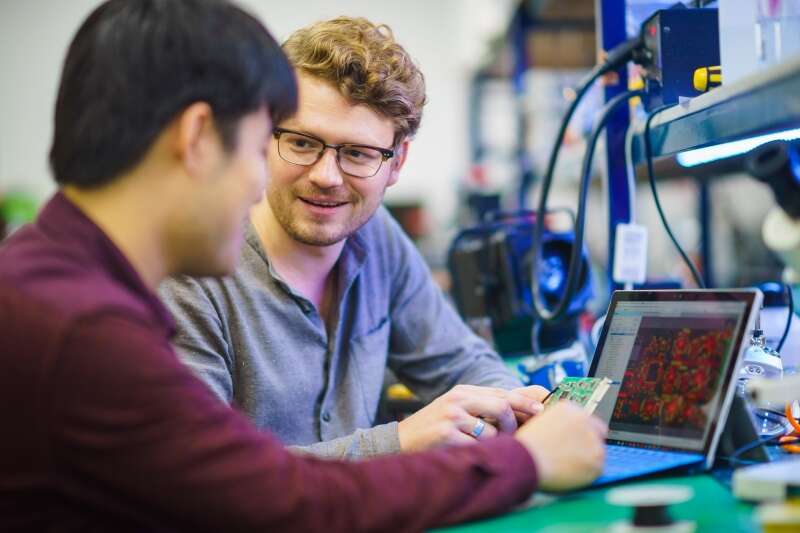

Smith and his team at EOS Space Systems have developed a laser tracking system – the only one of its kind – which allows them to monitor space debris much more accurately. If they see chunks are on a collision course, they can intervene.

One push is all it takes

The EOS satellite laser ranging facility at Mount Stromlo

“We’re building very big lasers which are strong enough to nudge space debris into a different orbit,” says Smith, who is a physicist. “The laser puts out a very concentrated stream of light. Light has energy and it has momentum and when that light hits an object, all that energy is absorbed into the target. Effectively, it has a push.

“It’s a small but measurable and predictable force, and because we can track things accurately, we only need a small push to make things miss each other. They sort of pass like two ships in the night and no one’s the worse for wear.”

Radar systems were previously used to track debris but are less accurate than EOS’s lasers, failing to register objects below a certain size (about 10 centimetres).

“With the invisible light that we use, we can see much smaller things, we can go down to two centimetres,” Smith says.

EOS has been building laser systems to track satellites for about 30 years. The company was spun out of an Australian government geodetic ranging program by Group CEO Ben Greene and three other colleagues. It now counts governments in Japan, the US and Europe, as well as international space agencies, satellite owners and defence agencies, as clients.

Satellite owners rely on EOS’s pinpoint tracking to tell them how high the collision threat is. They then make an informed decision about whether to move their satellite out of harm’s way.

“Often satellites just go off the air, and you’re never quite sure if it’s been hit by space debris or it’s just died spontaneously. It’s probably 50-50,” Smith says.

Growing amount of space junk

EOS Space Systems

Smith estimates there are 20,000 bits of space debris currently being tracked. This includes everything from fragments of astronauts’ clothing to remnants from launch vehicles.

“The first satellite, Sputnik, was launched in 1959 and ever since then we’ve been leaving stuff up there,” Smith says. “Prior to then, space was pristine: there was no space junk.

“There’s enough up there now that it’s a self-perpetuating problem,” he says. “We need to stop collisions and then start bringing down some of the junk.

“The oceans will probably recover if we stop polluting them, but space will not recover on its own.”

Over the years EOS has evolved from just space tracking. It now builds telescopes and observatory systems that are used around the world. It also manufactures remote-control weapon stations for armoured vehicles, where a person safely controls the weapon from inside the vehicle using a joystick.

Smith says this is a very successful component of the business today, with armed forces in Australia, Europe, Singapore and the Middle East using the weapon stations.

“We’re a state-of-the-art company,” Smith says. “We look for niches that people haven’t yet identified and develop a product so that by the time the customer realises they have a problem, we’ve got the solution.”

Taking out the trash

Space remains a passion for Smith – “Since I was a kid I’ve been interested in astronomy and science” – so he’s particularly pleased that Australia now has its own space agency.

Australia has always taken a leading role in trying to establish normal, reasonable behaviour on the use of space.

“We are world leaders in the downstream use of space information, such as meteorology and geoscience. Now we have a focal point for collaboration, leadership, guidance, monitoring and regulation.”

Smith firmly believes we can fix the space debris problem, despite more frequent crashes anticipated between tracked objects and an estimate suggesting that debris will triple by 2030.

“We just have to have the will and show the leadership to make it happen,” he says. “The issue is not to take ourselves back to the Stone Age and stop doing things but to find new technologies to clean it up.

“We have one solution but there surely are others."

Smith is confident that awareness is growing about the dangers of space debris, and more companies are stepping into the fray.

“If it’s going to make space clean again, then the more people working on it the better.”

What about using space harpoons, robot arms and giant nets to snag space junk and drag it back to Earth? Smith is all for it, although his solution is much simpler: Just make it an offence to dump in space.

Author: Maryanne Blacker

First published on australiaunlimited.com