Social Media: The New Frontier In Mental Health

South America is the angriest continent and Oceania the most joyful, according to millions of tweets fired off into the online world each day. That’s just one of many insights gleaned through the ‘We Feel’ tool, which analyses up to 32,000 tweets per minute. Developed in 2014 by Australia’s national science agency CSIRO in collaboration with Amazon Web Services, the tool is part of a ground-breaking initiative by the Black Dog Institute to explore whether social media can accurately map our emotions.

Social media is often deemed to present a carefully curated version of our lives. But according to Professor Helen Christensen, Director and Chief Scientist at the Black Dog Institute and leader of the Digital Dog research group, it might tell us more than we think when it comes to our mental health.

The Black Dog Institute has been working to reduce mental illness and the stigma surrounding it since 1985.

Leading the way in mental health reform

Professor Helen Christensen, Director and Chief Scientist at the Black Dog Institute © Australia Unlimited

After completing her PhD at the University of New South Wales in the late 80s, Christensen’s initial research focus was on ageing and memory. It was at this time she saw there was very little funding for Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) programs to treat depression, despite ample evidence of its efficacy, and that young people with mental health issues weren’t getting the help they needed.

More than two decades on, it’s an area that remains very close to her heart. “[Depression] hits people in their youth and robs them of so much,” she says. “I think, like everyone, we know people with mental health problems, people in our family, workmates. “And it just seems to me that we could do much better [in addressing the issue] than we are.”

Depression is the second leading cause of disability and disease in youth globally. In Australia, suicide is the leading cause of death in young people – and these figures aren’t decreasing. Christensen says it’s been estimated that a serious mental illness costs Australia A$34,000 per person per year. “It really is a huge, huge burden.”

In 1998, when many of us were just setting up our Hotmail accounts and dubiously discovering chat rooms, Christensen and a group of fellow researchers were creating MoodGYM – an interactive online CBT program that helps people deal with depression and anxiety. The program received global recognition and by 2014 more than 800,000 people had registered. “That program was phenomenally successful,” says Christensen. “People just leapt onto it, all around the world. That was the start of my interest in e-health.”

Then, she says, social media and smartphones came along and “completely revolutionised everything”.

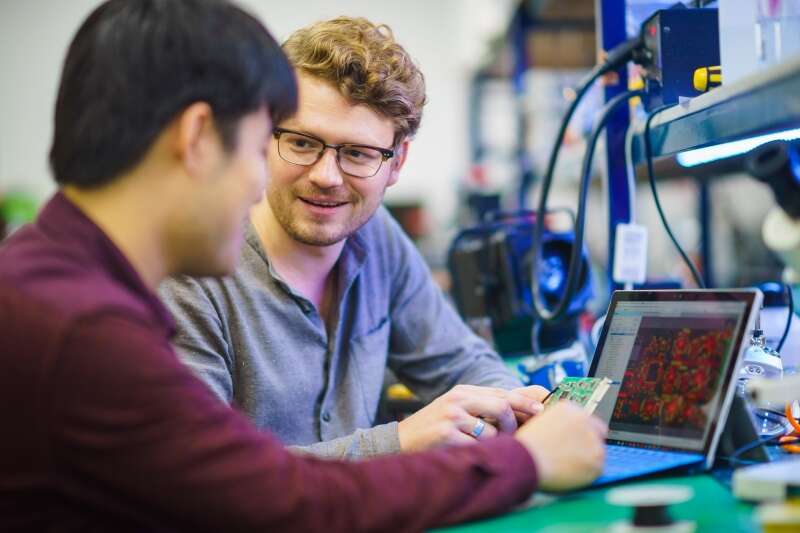

Digital technology: Mental health's new frontier

Digital technology: mental health's new frontier © Warren Wong, Australia Unlimited

A Professor of Mental Health at the University of New South Wales and Chief Investigator for the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Suicide Prevention, Christensen is internationally recognised as a pioneer in e-mental health, one of the fastest growing areas in mental health. Christensen and the Digital Dog team have a lot on their plates. They’re developing and testing a suite of apps, websites and games to help lower depression and suicide risk, reduce stress and promote wellbeing.

Less than 35 per cent of Australians with a mental illness seek help, and 60 per cent don’t have access to any treatment, says Christensen. So there is huge potential to increase access to treatment through digital and online technologies. Compared with traditional face- to-face support, it gives people more flexibility, choice and convenience. It may also be the only option for someone who feels stigmatised.

Through the We Feel project, Christensen and her pioneering team initially used the technology to track the world’s emotional pulse in real time. They watched as emotions fluctuated and joy or anger spiked during events such as political elections and sports games. “We used it to look at the impact of Robin Williams’s death around the world. We compared the sadness curves across the UK, US and Australia,” says Christensen. “You had different strengths of emotions, but essentially you could just see a wave of shock and then sadness.”

While it’s fascinating to observe the emotional patterns of cities, countries and continents, Christensen, as ever, is aiming higher. She wants to use We Feel at an individual level. “For example, we want to know how we can stop people from being at high risk of suicide so we can intervene,” she says. “But it’s harder at an individual level to pick up a digital footprint that means something. And that’s the excitement of where we’re going now.”

Christensen is working with colleagues and collaborators to develop technology and algorithms that can accurately predict and help manage mental health risk through social media. Recently the team started tracking people who blog in depression communities (with their consent, as with all Digital Dog’s initiatives) and measuring their mental health symptoms in tandem with their blogging to find potential correlations.

Innovating to save lives

We Feel is just one of a growing suite of initiatives and trials at Digital Dog. Christensen is particularly excited about three of them. These include SHUTi, an automated online insomnia program recently trialed in conjunction with Virginia University. SHUTi successfully stopped depression from developing or getting worse in participants and the effects have been sustained for 18 months so far.

Christensen has also seen great results from trials of an online game that delivers CBT to Year 12 students six months before taking their final exams, and an app that delivers Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to young Indigenous Australians in the context of Indigenous values and metaphors.

Designing a brighter future

Christensen is a woman with a big vision: a world where mental health problems are detected and prevented, and everyone suffering mental illness can get access to treatment. “[Digital Dog has] so many proposals in for funding. Basically we’re into world domination,” she jokes. But an ambitious new plan to run a study of 20,000 young Australians to learn more about social media’s potential is certainly no joke.

Does the future of mental health lie in early detection and prevention through smartphones, apps and social media? Can our tweets and blog posts give an accurate picture of our mental health and raise the alarm bell when we need help?

Christensen is well and truly on the case. Watch this digital space.

Author: Ruby Lohman

First published on australiaunlimited.com